*****

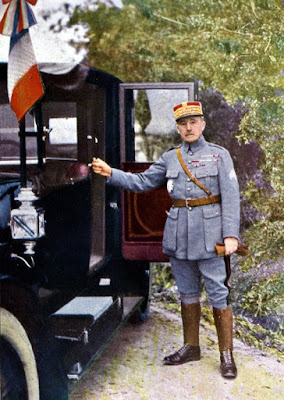

General Falkenhayn

Last month's note from the United States to Germany following the attack on the British channel steamer Sussex threatened a break in diplomatic relations unless Germany agreed to abide by "cruiser rules" when attacking passenger and merchant shipping. In Germany, General Falkenhayn, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, urged rejection of the American demand, arguing that the unrestricted submarine campaign offered the best hope of countering the British naval blockade. Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, however, persuaded the Kaiser to adopt a more conciliatory policy. The German reply came in two notes. The first, dated May 4, stated that the German submarine commanders had been ordered to conduct operations in accordance with cruiser rules. The second note, dated May 8, addressed the specific case of the Sussex. It accepted the evidence that the damage to the steamer had been caused by a German torpedo, expressed regret, stated that the submarine commander had been punished, and offered an indemnity.

Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg

The May 4 note announcing the new German policy requiring submarines to observe cruiser rules stated that Germany expected the United States "will now demand and insist that the British Government shall forthwith observe the rules of international law universally recognized before the war, as are laid down in the notes presented by the Government of the United States to the British Government Dec. 28, 1914 and Nov. 5, 1915." Should those efforts fail, "the German Government would then be facing a new situation in which it must reserve to itself complete liberty of decision."

Secretary of State Lansing

The United States replied on May 8 in a note drafted by Secretary of State Robert Lansing and reviewed and approved by President Wilson. It welcomed the German government's new policy while rejecting the stated condition: "[The United States] takes it for granted that the Imperial German Government does not intend to imply that the maintenance of its newly announced policy is in any way dependent upon the course or result of diplomatic negotiations between the Government of the United States and the Government of any other belligerent Government, notwithstanding the fact that certain passages in [its note] might appear to be susceptible of that construction. . . . [The United States] cannot for a moment entertain, much less discuss, a suggestion that respect by German naval authorities for the rights of citizens of the United States upon the high seas should in any way or in the slightest degree be made contingent upon the conduct of any other Government affecting the rights of neutrals and noncombatants. Responsibility in such matters is single, not joint; absolute, not relative." Lansing has let it be known that he does not expect any further replies from Germany, and that unless Germany indicates otherwise it will be assumed that she accepts the American position as stated.

*****

When Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the Commander in Chief of the German High Seas Fleet, received the Kaiser's order to observe cruiser rules in encounters with merchant shipping, he recalled all submarines to port and began laying plans for a major surface action designed to destroy a substantial part of the British fleet without great risk to his own. The plan was for Admiral Franz von Hipper's fast scouting group of battle cruisers to conduct a raid on the North Sea coast of England, drawing the British battle cruisers commanded by Admiral David Beatty from their anchorage in the Firth of Forth. Submarines would attack and sink as many as possible of the British ships; the German battle cruisers would then engage them and lure them toward the guns of the High Seas Fleet's dreadnoughts as they emerged from their anchorage in the Jade River.

Unfortunately for the German plan, the code breakers in Room 40 of the British Admiralty had intercepted and decoded German wireless messages implementing the plan, and were therefore aware that a major operation of some kind was being planned for the end of May. Thus by the time the High Seas Fleet was under way, and before the German submarines were on station, the Grand Fleet under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe had left its anchorages at Scapa Flow and Cromarty Firth and Admiral Beatty's battle cruisers had cleared the Firth of Forth. Among the officers in the Grand Fleet was Prince Albert, the second son of King George V, a midshipman aboard the dreadnought HMS Collingwood. As the largest battle fleets in the world converged on an area in the North Sea off the coast of Denmark, the stage was set for a double ambush.

Admiral Beatty's battle cruisers came within range of Admiral Hipper's battle cruisers at about 2:30 in the afternoon of May 31. The Fifth Battle Squadron, consisting of four battleships under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas, had been assigned to reinforce the battle cruisers, but a communications failure caused it to fall behind. Rather than wait for the battleships, Beatty took his battle cruisers toward the German battle cruisers at full speed, and despite the greater range of the British guns delayed opening fire until he was within range of Hipper's guns. Hipper was the first to open fire, reversing course to draw Beatty toward the German dreadnoughts approaching from the south. As the two battle cruiser squadrons raced on parallel courses to the southeast, they engaged in a ferocious gunnery duel in which two of Beatty's ships, HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary, were hit by gunfire and destroyed by magazine explosions. The sudden loss of two battle cruisers, followed by a report (which later proved inaccurate) that a third, HMS Princess Royal, had also blown up, caused Beatty to turn to his flag captain and remark, "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today, Chatfield."

At about 4:30, Beatty's advance screen reported the presence of the main body of the High Seas Fleet approaching from the south. Realizing the trap, Beatty reversed course and headed north to draw the Germans toward Jellicoe and the main force of British dreadnoughts. As Beatty rejoined Jellicoe, and as Hipper and Scheer came within range, Jellicoe deployed his dreadnoughts to the east, changing their formation from the multiple columns in which they had been approaching the area into a single battle line that unmasked all of their main batteries (thus "crossing the T" in naval parlance). As each ship swung into line, it opened fire. When Scheer realized he was confronting the main British fleet and that he was in a vastly inferior tactical position, he ordered his fleet immediately to reverse course, disappearing over the horizon to the southwest. As Jellicoe headed south to keep his ships between the German fleet and the Danish coast, Scheer tried to catch the British fleet off guard by turning back to the east and opening fire. Once again, however, Scheer's T was crossed as he confronted the full weight of fire from the Grand Fleet's battle line. As he began suffering serious damage, Scheer reversed course again and withdrew behind a torpedo attack launched by his destroyers. Jellicoe could have evaded the torpedoes by turning toward them while continuing to pursue Scheer and keeping the German ships within range, but he took the more cautious

approach of turning his fleet away from the torpedoes. By doing so, he allowing Scheer to withdraw again out of range of the British guns.

As night fell, Jellicoe continued on a southerly course to cut off the Germans' anticipated escape route and stationed a screen of cruisers and destroyers to the rear of his main fleet to guard against destroyer attacks. During the night, however, Scheer turned his fleet to the southeast toward Horns Reef, off the Danish coast. If he could reach Horns Reef without being intercepted by Jellicoe, he could enter a swept channel and escape through the minefields to his base at Heligoland Island, at the mouth of the Jade. Throughout the night the Grand Fleet heard gunfire and saw flashes to the north, but interpreted it as coming from attacks on the rearguard screen by German destroyers. British ships that were nearer the action and aware of what was happening failed to report it, so the Grand Fleet maintained its southerly course. By the time the sky began to lighten (about 2:00 a.m. -- nights are short this time of year in those latitudes), Scheer had crossed the wake of the Grand Fleet and was nearing Horns Reef. By 3:30 he had passed the Horns Reef lightship and entered the swept channel. The High Seas Fleet had been saved from almost certain destruction.

The British lost fourteen ships in the Battle of Jutland: three battle cruisers, three armored cruisers and eight destroyers. The German Navy lost eleven ships: one battle cruiser, one predreadnought battleship, four light cruisers and five destroyers. 3,058 German sailors were killed or wounded, while 6,768 British sailors lost their lives, many of the latter killed when their ships were destroyed in sudden magazine explosions with no opportunity for rescue. Despite the German advantage in numbers of ships and sailors lost, at the battle's conclusion the German High Seas Fleet was back in the Jade where it had started, and the Grand Fleet still dominated the North Sea.

Admiral Beatty

Unfortunately for the German plan, the code breakers in Room 40 of the British Admiralty had intercepted and decoded German wireless messages implementing the plan, and were therefore aware that a major operation of some kind was being planned for the end of May. Thus by the time the High Seas Fleet was under way, and before the German submarines were on station, the Grand Fleet under the command of Admiral John Jellicoe had left its anchorages at Scapa Flow and Cromarty Firth and Admiral Beatty's battle cruisers had cleared the Firth of Forth. Among the officers in the Grand Fleet was Prince Albert, the second son of King George V, a midshipman aboard the dreadnought HMS Collingwood. As the largest battle fleets in the world converged on an area in the North Sea off the coast of Denmark, the stage was set for a double ambush.

HMS Queen Mary Explodes at Jutland

Admiral Beatty's battle cruisers came within range of Admiral Hipper's battle cruisers at about 2:30 in the afternoon of May 31. The Fifth Battle Squadron, consisting of four battleships under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas, had been assigned to reinforce the battle cruisers, but a communications failure caused it to fall behind. Rather than wait for the battleships, Beatty took his battle cruisers toward the German battle cruisers at full speed, and despite the greater range of the British guns delayed opening fire until he was within range of Hipper's guns. Hipper was the first to open fire, reversing course to draw Beatty toward the German dreadnoughts approaching from the south. As the two battle cruiser squadrons raced on parallel courses to the southeast, they engaged in a ferocious gunnery duel in which two of Beatty's ships, HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary, were hit by gunfire and destroyed by magazine explosions. The sudden loss of two battle cruisers, followed by a report (which later proved inaccurate) that a third, HMS Princess Royal, had also blown up, caused Beatty to turn to his flag captain and remark, "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today, Chatfield."

Admiral Jellicoe

At about 4:30, Beatty's advance screen reported the presence of the main body of the High Seas Fleet approaching from the south. Realizing the trap, Beatty reversed course and headed north to draw the Germans toward Jellicoe and the main force of British dreadnoughts. As Beatty rejoined Jellicoe, and as Hipper and Scheer came within range, Jellicoe deployed his dreadnoughts to the east, changing their formation from the multiple columns in which they had been approaching the area into a single battle line that unmasked all of their main batteries (thus "crossing the T" in naval parlance). As each ship swung into line, it opened fire. When Scheer realized he was confronting the main British fleet and that he was in a vastly inferior tactical position, he ordered his fleet immediately to reverse course, disappearing over the horizon to the southwest. As Jellicoe headed south to keep his ships between the German fleet and the Danish coast, Scheer tried to catch the British fleet off guard by turning back to the east and opening fire. Once again, however, Scheer's T was crossed as he confronted the full weight of fire from the Grand Fleet's battle line. As he began suffering serious damage, Scheer reversed course again and withdrew behind a torpedo attack launched by his destroyers. Jellicoe could have evaded the torpedoes by turning toward them while continuing to pursue Scheer and keeping the German ships within range, but he took the more cautious

approach of turning his fleet away from the torpedoes. By doing so, he allowing Scheer to withdraw again out of range of the British guns.

Maps of the Battle

As night fell, Jellicoe continued on a southerly course to cut off the Germans' anticipated escape route and stationed a screen of cruisers and destroyers to the rear of his main fleet to guard against destroyer attacks. During the night, however, Scheer turned his fleet to the southeast toward Horns Reef, off the Danish coast. If he could reach Horns Reef without being intercepted by Jellicoe, he could enter a swept channel and escape through the minefields to his base at Heligoland Island, at the mouth of the Jade. Throughout the night the Grand Fleet heard gunfire and saw flashes to the north, but interpreted it as coming from attacks on the rearguard screen by German destroyers. British ships that were nearer the action and aware of what was happening failed to report it, so the Grand Fleet maintained its southerly course. By the time the sky began to lighten (about 2:00 a.m. -- nights are short this time of year in those latitudes), Scheer had crossed the wake of the Grand Fleet and was nearing Horns Reef. By 3:30 he had passed the Horns Reef lightship and entered the swept channel. The High Seas Fleet had been saved from almost certain destruction.

The British lost fourteen ships in the Battle of Jutland: three battle cruisers, three armored cruisers and eight destroyers. The German Navy lost eleven ships: one battle cruiser, one predreadnought battleship, four light cruisers and five destroyers. 3,058 German sailors were killed or wounded, while 6,768 British sailors lost their lives, many of the latter killed when their ships were destroyed in sudden magazine explosions with no opportunity for rescue. Despite the German advantage in numbers of ships and sailors lost, at the battle's conclusion the German High Seas Fleet was back in the Jade where it had started, and the Grand Fleet still dominated the North Sea.

*****

General Nivelle

On land, the war continued this month with undiminished ferocity. On May 15 the Austrians mounted a major offensive on the Trentino Front. By month's end they had advanced twelve miles through mountainous terrain and captured 30,000 Italian prisoners. On the Western Front, British preparations continued for a major offensive on the Somme. On May 1 General Petain was promoted to command of the Central Army Group at Bar-le-Duc, and General Robert Nivelle replaced him at Verdun as commander of the Second Army. On May 22 French forces attacked the German lines in the area around Fort Douaumont and succeeded in driving the Germans back and occupying a portion of the fort itself. Two days later, however, the Germans counterattacked and regained most of the lost ground. On the left bank of the Meuse, the German army renewed its attack on Mort Homme and gained the crest on May 29 after days of bloody fighting. Little advantage was gained, however, as more crests remained between the Germans and the city. In Mesopotamia, the British and Indian soldiers who surrendered last month at Kut al Amara have been marched to Baghdad and beyond through the desert toward Anatolia in conditions of extreme privation and brutality. Thousands have died along the way. Meanwhile in the chanceries of Europe, the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, which anticipates Allied victory over the Ottoman Empire and divides its lands among areas of British, French and Russian control and spheres of influence (see last month's installment of this blog), was finalized in an exchange of notes on May 16.

*****

Patrick Pearse

The 1914 Defence of the Realm Act gives "His Majesty in Council" and "members of His Majesty's forces and other persons acting in his behalf" the power to enact regulations "for securing the public safety and defence of the realm" and authorizing "the trial by courts-martial . . . and punishment of persons committing offences against the regulations." Pursuant to the Act, the leaders of last month's uprising in Dublin have been tried by a field general courts-martial, found guilty, and executed by firing squad in the courtyard of Kilmainham Prison. The executions took place between May 3 and May 12, and included all seven of the signers of the Proclamation of the Republic that Patrick Pearse read from the steps of the General Post Office on Easter Monday. On May 15 in London, Sir Roger Casement, who was arrested on the coast of Ireland on April 21 after being put ashore from a German submarine, appeared in Bow Street Police Court for a preliminary hearing on a charge of treason. After a two-day proceeding, he was bound over for trial.

*****

General Obregon

Relations between the United States and Mexico have reached a new low. The month began on a hopeful note, as extensive negotiations between Generals Scott and Funston for the United States and General Obregon for the Mexican government of Emilio Carranza reached a tentative agreement: that American troops would be withdrawn from Mexican territory in light of the fact that General Pershing's Punitive Expedition had largely accomplished its mission and that the Carranza forces appeared capable of continuing the pursuit of Villa. Before the agreement could be finalized, however, a band of Villistas crossed the Rio Grande and attacked settlements in the Big Bend area of Texas, killing and kidnapping American citizens. Additional American troops were sent to the area and a contingent under Colonel Frederick W. Sibley was sent across the border in pursuit, advancing over 180 miles into Mexico and killing some of the bandits before returning two weeks later to American soil. Although the United States expressed its willingness to finalize the agreement and continue the withdrawal of American troops, and although General Obregon continued to urge his government to agree, the Carranza government took a harder line. On May 31, it delivered a lengthy note to Washington charging that the United States had acted in bad faith and demanding the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of American troops from Mexican territory. The general opinion in Washington is that the note, while insulting in tone, is less threatening than it appears and was drafted mainly for domestic consumption.

*****

The May 13 Preparedness Parade in Manhattan

As the American political parties prepare for their presidential nominating conventions in June, war and preparedness are foremost in the public mind. On May 13 Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt joined a huge preparedness parade that stretched for miles down Fifth Avenue in New York City. 125,683 marchers and 200 bands paraded by the reviewing stand as General Leonard Wood and Mayor John Purroy Mitchel looked on. Not far away at his home in Oyster Bay, former president Roosevelt greeted a crowd of well-wishers made up of Boy Scouts from nearby towns and a men's bible class from the Oyster Bay Methodist Church. On May 19 at the Opera House in Detroit, Colonel Roosevelt delivered a major speech on the subject of preparedness. He focused his remarks on Henry Ford, the outspoken pacifist and winner of this year's Michigan Republican primary, comparing him and other pacifists to the Copperheads of the Civil War who, he said, would have "purchased peace at the moment by ignoble submission to wrong, by ignoble cowardice."

President Taft With the Staff of the League to Enforce Peace

The League to Enforce Peace was formed last year by a group of influential opinion leaders including former President William Howard Taft, who continues to lead the League as its president. (See the July 1915 installment of this blog). On May 27 President Wilson addressed a meeting of the League at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. In his most important foreign policy address since the outbreak of the war in Europe, the president declared that the United States must have a say in the settlement of the European war. He announced that the United States is willing to join a league of nations formed to safeguard freedom of the seas, protect small states from aggression, and stop wars that are begun without giving the world an opportunity to weigh in on the causes.

Pamphlets for Billy Sunday's Revival

On the day President Wilson addressed the League to Enforce Peace, a crowd of 2,500, most of them brought from New York City by three special trains, assembled at Sagamore Hill for a rally in support of Theodore Roosevelt's candidacy for president. He left the next day for a western speaking tour, supposedly non-political but with the inevitable effect of promoting his candidacy in advance of next month's Republican convention in Chicago. On Memorial Day, a crowd of 50,000 met his train at Kansas City's new Union Station, and thousands more cheered and waved American flags as his motorcade took him to the Muehlebach Hotel for a dinner hosted by the Commercial Club. Evangelist Billy Sunday, who is conducting a revival in Kansas City, sat at Roosevelt's right hand and pledged his support. That evening Roosevelt addressed a capacity crowd at Convention Hall. The title of his speech was "A Message to All Americans," but he made clear that he had nothing to say to the "peace at any price men" who would prize "peace above duty" and "love of money getting before devotion to country." The next day in the pro-German city of St. Louis, he denounced the National German-American Alliance as an "anti-American Alliance" and said he welcomed its opposition.

May 1916 – Selected Sources and Recommended Reading

Contemporary Periodicals:

Contemporary Periodicals:

American Review of Reviews, June and July 1916

New York

Times, May 1916

Books and Articles:

A. Scott Berg, Wilson

Britain at War Magazine, The Third Year of the Great War: 1916

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis 1911-1918

John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography

John Milton Cooper, Jr., The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis 1911-1918

John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography

John Milton Cooper, Jr., The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt

Patrick Devlin, Too Proud to Fight: Woodrow Wilson's

Neutrality

John Dos Passos, Mr. Wilson's War

David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914-1922

Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life

Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History

Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History

Martin Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, Volume One: 1900-1933

Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill Volume III: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916

Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill Volume III: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916

Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, Decisions for War, 1914-1917

Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House

Paul Jankowski, Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War

Keith Jeffrey, 1916: A Global History

Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography

John Keegan, The First World War

David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society

Nicholas A. Lambert, Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War

John Keegan, The First World War

David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society

Nicholas A. Lambert, Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War

Arthur S. Link, Wilson: Confusions and Crises, 1915-1916

Arthur S. Link, Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era,

1910-1917

G.J. Meyer, A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918

Malise Ruthven, The Map ISIS Hates, New York Review of Books June 25, 2014

Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

J. Lee Thompson, Never Call Retreat: Theodore Roosevelt and the Great War

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History

The West Point Atlas of War: World War I