*****

Republicans Gathering at the Chicago Coliseum

The Republican Party approached its 1916 presidential nominating convention with the wounds of 1912 far from healed. Old Guard Republicans and Progressives alike realize that the election of Woodrow Wilson, only the second Democrat elected president since the Civil War, was made possible if not inevitable by former President Theodore Roosevelt's decision to lead the Progressives out of the Republican Party when he failed to defeat incumbent President Taft in the contest for the party's nomination (see the April through August 1912 installments of this blog). Both factions of the party were eager to repair the split if possible, but only on their own terms, and this year both sides' terms revolved around a single personality: Roosevelt himself, and his desire to return to the White House. Most of the Republicans who assembled at the Chicago Coliseum on June 7 regarded Roosevelt's actions in 1912 as a betrayal, and were adamantly opposed to his candidacy. Many of them preferred leaders who had remained with the party and supported President Taft in 1912, such as former Senator and Secretary of State Elihu Root and Iowa Senator Albert Cummins. Representatives of the two factions held meetings but failed to reach agreement, and by the time Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding gaveled the convention to order on June 7 sentiment was building in favor of Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, a moderately progressive former governor of New York who, having been appointed to the Court in 1910, had stayed clear of the 1912 split. Hughes was nominated on the third ballot, and former Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks was chosen as his running mate.

The Progressive Party, meeting nearby at the Auditorium Theatre, had gone to Chicago hoping to use its leverage to persuade the Republicans to reunite the party under Roosevelt's leadership. When they received word that Hughes's nomination was imminent, they held a vote and nominated Roosevelt as the Progressive Party's candidate. To their intense disappointment, Roosevelt immediately sent a telegram to the convention saying he "cannot accept [the nomination] at this time" because "I do not know the position of the candidate of the Republican Party on the vital questions of the day." He asked that his "conditional refusal to run be placed in the hands of the Progressive National Committee," and that if the Committee was satisfied with Mr Hughes' statements "when he makes them," it should "act accordingly and treat my refusal as definitely accepted." Even if the convention had been inclined to consider other candidates, Roosevelt's "conditional refusal" effectively foreclosed both his own nomination and that of anyone else. Two weeks later, in a letter to the Progressive National Committee, Roosevelt endorsed Hughes, saying that a third party campaign would be fruitless and "a move in the interest of the election of Mr.Wilson." On June 26, at a meeting in Chicago, after six hours of sometimes bitter debate, the Committee gave Hughes its official endorsement. The vote was 32 in favor of endorsing Hughes, six opposed, and nine not voting. A motion to substitute former Representative Victor Murdock of Kansas as the Progressive Party's presidential nominee was defeated by a vote of 32 to 15.

The events of this month are widely regarded as sounding the death knell of the Progressive Party as a political force separate from the Republicans. Also dead, at least for the time being, is the hope expressed by some of establishing "a second white man's party" in the South as a counterweight to the Democrats, who have dominated the politics of that region since the end of Reconstruction. For years the Republican Party in the South has been made up largely of Negroes, who are unable to vote due to restrictive state laws but remain a force to be reckoned with at Republican conventions. Roosevelt, in his pursuit of the Republican nomination in 1912, led an unsuccessful effort to seat "lily-white" delegations from Southern states, which he argued would more accurately represent actual Republican voters, rather than the "black and tan" delegations that supported President Taft. (Democratic Party conventions, of course, have always been "lily-white"). The demise of the Progressive Party this year removes a threat to Democratic hegemony in the South, leaving the politics of the region largely unchanged.

On June 1, by a vote of 47 to 22, the Senate confirmed the nomination of Louis D. Brandeis to fill the vacancy created by the death of Justice Joseph R. Lamar earlier this year. Justice Brandeis's confirmation brings the first Jewish justice to the Court and ends a four-month confirmation battle in which Brandeis was fiercely opposed by business interests and other conservative forces who feared his reputation as an advocate for progressive causes. Brandeis, who is known as the "peoples' attorney," has become famous for his use of the "Brandeis brief," in which he relies less on legal analysis than on data and opinions found in professional journals, treatises and statistical compilations, presented to show the social desirability of the result he is advocating.

Justice Hughes resigned from the Supreme Court on June 10 to accept the Republican nomination for president. President Wilson now has another vacancy to fill.

The week after the Republicans nominated Hughes, the Democratic Party held its convention at the St. Louis Coliseum. Unlike the Republicans, who entered their convention with several viable candidates, and very unlike the Democrats' own convention four years ago which held a record 46 ballots before nominating Woodrow Wilson, there was no suspense this year regarding the party's nominee. President Wilson entered the convention with no opposition to his renomination, the only question being how the party and its president would be portrayed to the nation as they entered the general election. The main threat to Wilson's reelection seemed to be summed up by the Republican convention's emphasis on Americanism, and on Roosevelt's criticism of Wilson for being too weak on preparedness and too timid in defending American interests -- that he was indeed "too proud to fight." To counter that criticism, the organizers of the convention had decorated the hall with hundreds of American flags and advised the delegates and speakers to emphasize patriotism at every opportunity. The keynote speaker, former Governor Martin Glynn of New York, went to the podium on June 14 intending to do just that. To respond to the Republican criticism that Wilson had failed to stand up for America's interests abroad, he was also armed with a number of examples from American history in which the United States had been challenged and even humiliated by other nations and resisted the temptation to resort to military force. Glynn intended to cite one or two of those cases as precedents before moving on to the patriotism theme, but his speech soon took an unexpected turn. His first example was an 1873 incident in which Spain seized an American ship en route to Cuba and executed its captain and many of its crew. Then he cited an 1891 attack on American sailors in Valparaiso, Chile, and numerous violations of American rights by European governments during the Civil War, adding in each case that none had led to war. The delegates and spectators in the auditorium cheered each example lustily. When he said he had more examples but would move on, the crowd insisted that he recite them all, and even made him repeat some of their favorites. Responding to the mood of his audience he obliged, and as he described each such incident the crowd shouted "What did we do?" His answer in each case, greeted by ecstatic cheers, was "We didn't go to war!" Every mention of patriotism, in contrast, was greeted only with polite applause.

Victor Murdock

The Progressive Party, meeting nearby at the Auditorium Theatre, had gone to Chicago hoping to use its leverage to persuade the Republicans to reunite the party under Roosevelt's leadership. When they received word that Hughes's nomination was imminent, they held a vote and nominated Roosevelt as the Progressive Party's candidate. To their intense disappointment, Roosevelt immediately sent a telegram to the convention saying he "cannot accept [the nomination] at this time" because "I do not know the position of the candidate of the Republican Party on the vital questions of the day." He asked that his "conditional refusal to run be placed in the hands of the Progressive National Committee," and that if the Committee was satisfied with Mr Hughes' statements "when he makes them," it should "act accordingly and treat my refusal as definitely accepted." Even if the convention had been inclined to consider other candidates, Roosevelt's "conditional refusal" effectively foreclosed both his own nomination and that of anyone else. Two weeks later, in a letter to the Progressive National Committee, Roosevelt endorsed Hughes, saying that a third party campaign would be fruitless and "a move in the interest of the election of Mr.Wilson." On June 26, at a meeting in Chicago, after six hours of sometimes bitter debate, the Committee gave Hughes its official endorsement. The vote was 32 in favor of endorsing Hughes, six opposed, and nine not voting. A motion to substitute former Representative Victor Murdock of Kansas as the Progressive Party's presidential nominee was defeated by a vote of 32 to 15.

The events of this month are widely regarded as sounding the death knell of the Progressive Party as a political force separate from the Republicans. Also dead, at least for the time being, is the hope expressed by some of establishing "a second white man's party" in the South as a counterweight to the Democrats, who have dominated the politics of that region since the end of Reconstruction. For years the Republican Party in the South has been made up largely of Negroes, who are unable to vote due to restrictive state laws but remain a force to be reckoned with at Republican conventions. Roosevelt, in his pursuit of the Republican nomination in 1912, led an unsuccessful effort to seat "lily-white" delegations from Southern states, which he argued would more accurately represent actual Republican voters, rather than the "black and tan" delegations that supported President Taft. (Democratic Party conventions, of course, have always been "lily-white"). The demise of the Progressive Party this year removes a threat to Democratic hegemony in the South, leaving the politics of the region largely unchanged.

Justice Brandeis

On June 1, by a vote of 47 to 22, the Senate confirmed the nomination of Louis D. Brandeis to fill the vacancy created by the death of Justice Joseph R. Lamar earlier this year. Justice Brandeis's confirmation brings the first Jewish justice to the Court and ends a four-month confirmation battle in which Brandeis was fiercely opposed by business interests and other conservative forces who feared his reputation as an advocate for progressive causes. Brandeis, who is known as the "peoples' attorney," has become famous for his use of the "Brandeis brief," in which he relies less on legal analysis than on data and opinions found in professional journals, treatises and statistical compilations, presented to show the social desirability of the result he is advocating.

Justice Hughes resigned from the Supreme Court on June 10 to accept the Republican nomination for president. President Wilson now has another vacancy to fill.

*****

Governor Martin Glynn

The week after the Republicans nominated Hughes, the Democratic Party held its convention at the St. Louis Coliseum. Unlike the Republicans, who entered their convention with several viable candidates, and very unlike the Democrats' own convention four years ago which held a record 46 ballots before nominating Woodrow Wilson, there was no suspense this year regarding the party's nominee. President Wilson entered the convention with no opposition to his renomination, the only question being how the party and its president would be portrayed to the nation as they entered the general election. The main threat to Wilson's reelection seemed to be summed up by the Republican convention's emphasis on Americanism, and on Roosevelt's criticism of Wilson for being too weak on preparedness and too timid in defending American interests -- that he was indeed "too proud to fight." To counter that criticism, the organizers of the convention had decorated the hall with hundreds of American flags and advised the delegates and speakers to emphasize patriotism at every opportunity. The keynote speaker, former Governor Martin Glynn of New York, went to the podium on June 14 intending to do just that. To respond to the Republican criticism that Wilson had failed to stand up for America's interests abroad, he was also armed with a number of examples from American history in which the United States had been challenged and even humiliated by other nations and resisted the temptation to resort to military force. Glynn intended to cite one or two of those cases as precedents before moving on to the patriotism theme, but his speech soon took an unexpected turn. His first example was an 1873 incident in which Spain seized an American ship en route to Cuba and executed its captain and many of its crew. Then he cited an 1891 attack on American sailors in Valparaiso, Chile, and numerous violations of American rights by European governments during the Civil War, adding in each case that none had led to war. The delegates and spectators in the auditorium cheered each example lustily. When he said he had more examples but would move on, the crowd insisted that he recite them all, and even made him repeat some of their favorites. Responding to the mood of his audience he obliged, and as he described each such incident the crowd shouted "What did we do?" His answer in each case, greeted by ecstatic cheers, was "We didn't go to war!" Every mention of patriotism, in contrast, was greeted only with polite applause.

Senator James Firing Up the Democrats in St. Louis

With Glynn's speech, to the discomfort of President Wilson in Washington and the party leadership in St. Louis, the theme of the convention shifted from patriotism to pacifism. The next day, it was the turn of the convention's permanent chairman to speak. Senator Ollie James of Kentucky, taking his cue from his audience's reaction to Glynn's address the day before, roused the convention again with a stem-winding tribute to the president's avoidance of war: "Tonight twenty million American fathers will gather around an unbroken family fireside with their wives at their sides and their children around their knees and contrast that with the Old World, the world of broken firesides and gloom and mourning upon every hand. If that is evil and vacillating, may God prosper it and teach it to the rulers of the Old World." The climax of his speech brought the convention to its feet with cheers so loud the delegates insisted he repeat it, which he did to another round of tumultuous cheers: "Without orphaning a single American child, without widowing a single American mother, without firing a single gun or shedding a single drop of blood, he wrung from the most militant spirit that ever brooded above a battlefield the concession of American demands and American rights."

Bryan and His Wife In New York Last Year

Former presidential candidate and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan was in attendance at the convention as a reporter. After Senator James's speech, the convention voted unanimously to suspend the rules and invite Bryan to the podium. He told them "I join the American people in thanking God that we have a President who does not want this nation plunged into this war." The next day the convention nominated President Wilson and Vice President Marshall by acclamation. Then it adopted a platform written by President Wilson himself, to which the Platform Committee had added a single sentence: "In particular, we commend to the American people the splendid diplomatic victories of our great President, who has preserved the vital interests of our Government and its citizens, and kept us out of war."

Americanism, patriotism, preparedness and opposition to "hyphenated" Americans still seem to be themes that all candidates agree upon. Hughes, in a statement made on June 13 to newspaper men in New York in response to questions raised by his endorsement by the German-American Association, said "my attitude is one of undiluted Americanism, and anybody who supports me is supporting an out-and-out American and an out-and-out American policy and nothing else." The same day, in an address to the graduating class at West Point, President Wilson said he believes the great majority of foreign-born citizens are loyal, and that those "who have loved other countries more than they have loved the country of their adoption" are relatively few in number.

*****

Ambassador Arredondo

As his fellow Democrats were praising him for keeping the United States out of the war in Europe, President Wilson was on the brink of war with Mexico. In its note delivered May 31, the de facto Mexican government led by Venustiano Carranza accused the United States of bad faith and demanded immediate withdrawal of American troops, saying that otherwise the Mexican government would have "no further recourse than to defend its territory by an appeal to arms." The American reply was delivered by Secretary of State Lansing to Mexican Ambassador Eliseo Arredondo on June 20. It rejected the Mexican demands, stating that United States troops were sent into Mexican territory for the limited purpose of protecting American lives and property, and only because the de facto government had failed to fulfill its international obligation to do so. It warned that if the Carranza regime continued to ignore that obligation and carry out its threat of an "appeal to arms," it would "lead to the gravest consequences." Delivering copies of the note to other Latin American envoys in Washington the next day, Lansing assured them that the United States had no territorial ambitions or desire to interfere in Mexico's domestic affairs, and that it was taking this position only "to end the conditions which menace our national peace and the safety of our citizens."

Captain Boyd

The very day that those assurances were being made and the contents of the American note were appearing in newspapers in the United States and Mexico, the most serious military confrontation of the expedition was taking place in Carrizal, a small town near Villa Ahumada, about 100 miles south of El Paso and 90 miles east of General Pershing's headquarters at Colonia Dublan, in the Mexican State of Chihuahua. Pershing had sent two troops of the Negro 10th Cavalry to Villa Ahumada under the command of Captain Charles Boyd to investigate reports that Mexican troops were concentrating there. Because General Trevino, the Mexican commander in Chihuahua, had advised Pershing that he was under orders to resist the movement of American troops in any direction other than north, Pershing instructed Boyd to gather information but to avoid a fight. As the American troops neared Carrizal, the local Mexican commander General Felix Gomez advised Boyd that any attempt to proceed through Carrizal and into Villa Ahumada would be resisted. Boyd, ignoring this threat as well as his orders to avoid a fight, ordered his troops to proceed. A firefight ensued, in which fourteen Americans and thirty Mexicans were killed, including Captain Boyd and General Gomez. The Americans were turned back and twenty-five American soldiers were captured.

June 26 Anti-War Newspaper Advertisement

When it received word of the battle in Carrizal, the Wilson Administration prepared to take aggressive military action to protect American troops in Mexico and recover the American prisoners. By June 28, President Wilson had drafted a message to Congress reporting on the situation in Mexico and asking for authorization to use the armed forces as he deemed necessary to protect the border and ensure the establishment in Mexico of a constitutional government able and willing to preserve order. Before the message was delivered, however, the facts changed. That evening, news reports arrived in Washington that General Trevino had ordered the release of the American prisoners and arranged for their transportation to the border. Meanwhile a pacifist group, the American Union Against Militarism, had published an advertisement in major newspapers throughout the United States arguing that Mexican resistance to the American incursion into Mexican territory was not a valid excuse for war. The White House was inundated with hundreds of telegrams, increasing in number with the news that the American prisoners had been released and running ten to one against taking military action against Mexico. President Wilson signaled a change of course when he addressed the Associated Advertising Clubs in Philadelphia on June 29 and the New York Press Club on June 30. In his impromptu talk at the Advertising Clubs he said that America should be ready "to vindicate at whatever cost the principles of liberty, of justice, and of humanity to which we have been devoted from the first." Responding to cheers, he said "You cheer the sentiment, but do you realize what it means? It means that you have not only got to be just to your fellow men, but as a nation you have got to be just to other nations. It comes high. It is not an easy thing to do." In his prepared speech at the Press Club the next day he asked "Do you think the glory of America would be enhanced by a war of conquest in Mexico? Do you think that any act of violence by a powerful nation like this against a weak and distracted neighbor would reflect distinction upon the annals of the United States?" He was greeted with enthusiastic applause when he said "I have constantly to remind myself that I am not the servant of those who wish to enhance the value of their Mexican investments, that I am the servant of the rank and file of the people of the United States." Referring to the many letters he had received in recent days, he said "there is but one prayer in all of these letters: 'Mr. President, do not allow anybody to persuade you that the people of this country want war with anybody.'"

For the time being, it appears that the threat of another Mexican War has receded.

*****

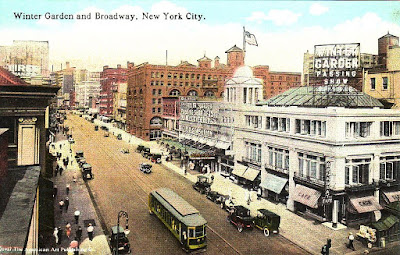

The Winter Garden Theatre

Musical

revues have become annual summer events on Broadway. The Ziegfeld

Follies of 1916 opened at the New Amsterdam Theatre on June 12. It

included music by Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin; featured players

included Fanny Brice, Marion Davies and Bert Williams. Uptown at the

Winter Garden Theatre, The Passing Show of 1916, produced by Lee and

Jacob Shubert, opened on June 22. The most popular of the many songs in

the production is Pretty Baby, performed here by Billy Murray (click to

play):

*****

General Brusilov

The war in Europe is reaching new levels of intensity and slaughter. At Verdun the Germans captured Fort Vaux, on the east bank of the Meuse, on June 7 after a three-month siege. They followed that success on June 23 with an attack on the French defenses in the nearby sector from Fleury to Souville, this time using a new poison gas, phosgene. As the attack intensified, the Commander of the French Second Army, General Robert Nivelle, ended an Order of the Day with the exhortation "They shall not pass!" The Germans took Fleury, but were turned back short of Fort Souville, one of two forts between the German Army and the city of Verdun that remain in French hands. As the struggle between the German and French armies continues at Verdun, major offensives have begun on other fronts. On June 24, in an operation designed in part to relieve the pressure on Verdun, an Allied offensive under British General Sir Douglas Haig began on June 24 with a 1,500-gun artillery barrage at the River Somme. At month's end the bombardment was still under way in preparation for an infantry assault. On the Eastern Front, a Russian army commanded by General Aleksei Brusilov began a major offensive on June 4 against Austria-Hungary. Among its strategic goals is to draw Austrian forces away from the Italian Front. It began with a massive artillery bombardment along a 200-mile front on the eastern frontier of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from the Pripet Marshes to the Bukovina, followed a few hours later by a swift advance that captured 26,000 Austrian troops. Lutsk fell to the Russians on June 8, Czernowitz on June 17.

*****

Sharif Hussein

Lord Kitchener

Field Marshal Herbert Horatio Kitchener, First Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, joined the British cabinet as Secretary of State for War shortly after the war began. In response to an invitation from Tsar Nicholas II last month to confer in person on war strategy, Kitchener departed King's Cross Station on June 4 for a journey to Russia. After arriving by train in Thurso, on the north coast of Scotland, he boarded a destroyer that carried him across Pentland Firth to Scapa Flow, the anchorage of the Grand Fleet. There he lunched with Admiral Jellicoe aboard his flagship and boarded the cruiser H.M.S. Hampshire for the trip to Russia. The planned route was north and east along the Arctic coast of Norway and Russia, through the Barents Sea to the port of Archangel on the White Sea, and thence by rail to Petrograd. Shortly after getting under way, Hampshire was struggling through heavy weather along the west coast of the Orkney Islands when it struck a mine, one of a number laid a week earlier by a German submarine. Almost everyone on board, including Kitchener and his staff, went down with the ship. Great Britain is in mourning for the loss of a universally admired war hero and symbol of the nation. David Lloyd George, the Minister of Munitions, has been named to succeed Kitchener as Secretary of State for War.

General Helmuth von Moltke was Chief of the German General Staff at the outbreak of the war. After the failure of the German armies to achieve a breakthrough at the Marne, he was replaced in September 1914 by General Erich von Falkenhayn. Moltke died of a heart attack on June 18 during a memorial service in the Reichstag for General Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz, the commander of Ottoman troops in Mesopotamia who died in April shortly before the British surrender at Kut Al Amara.

Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, who departed South Georgia Island on December 5, 1914, on an expedition to traverse the Antarctic continent from the Weddell Sea to McMurdo Sound by way of the South Pole, arrived at Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, on June 1. In January 1915, before his ship, the Endurance, could reach Antarctica, it was frozen in the ice in the Weddell Sea. In February, with the Antarctic winter approaching, Shackleton ordered his crew to convert Endurance to a winter station and wait for spring. When spring came, however, the movement of the ice began to crush the ship's hull, and on October 24 she had to be abandoned. Shackleton and his party camped on a large ice floe, hoping it would drift toward land. In April of this year the ice floe broke in two and Shackleton ordered his crew into lifeboats. Five days later they reached Elephant Island. He decided that his crew's only hope of rescue was to get back to South Georgia Island, 700 miles away across the Southern Ocean. He took the strongest of the lifeboats, named the James Caird after one of the expedition's sponsors, strengthened it further for the ocean voyage, and set sail with five of his crew. After fifteen days of remarkable seamanship and skillful navigation through frigid and stormy seas they reached the uninhabited southern coast of South Georgia Island. Rather than risk a further voyage around rocky shores and dangerous seas to the north side of the island, Shackleton decided to travel by land with two of his crew across the mountain ridges, glaciers and snow fields of the island's interior, a feat no one had previously attempted. Thirty-six hours later they reached the whaling station at Stromness, where they were greeted by the manager. Shackleton's first question was "Tell me, when was the war over?" The manager replied "The war is not over. Millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad."

After he reached the Falklands, Shackleton moved immediately to rescue the twenty-two men left behind on Elephant Island. He attempted to reach the island on a steamer placed at his disposal by the government of Uruguay, but was forced to turn back by extreme ice conditions. At month's end he is back in Port Stanley planning another rescue attempt, this time with an ice breaker. He is optimistic that the men on Elephant Island can survive on short rations, supplemented by the many penguins that inhabit the island.

In March of this year, Yuan Shih-Kai abandoned last year's declaration of the Chinese Empire and abdicated his title of Emperor. He tried to maintain control of the government as President, but faced increasing opposition, with several southern provinces declaring their independence. On June 6 Yuan died in Peking after a brief illness. Vice-President Li Yuan-Hung has succeeded to the presidency, and some of the rebellious provinces have rescinded their declarations of independence and declared their loyalty to the new government. Real power, however, appears to lie with regional warlords.

General von Moltke

General Helmuth von Moltke was Chief of the German General Staff at the outbreak of the war. After the failure of the German armies to achieve a breakthrough at the Marne, he was replaced in September 1914 by General Erich von Falkenhayn. Moltke died of a heart attack on June 18 during a memorial service in the Reichstag for General Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz, the commander of Ottoman troops in Mesopotamia who died in April shortly before the British surrender at Kut Al Amara.

Launching the James Caird

Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, who departed South Georgia Island on December 5, 1914, on an expedition to traverse the Antarctic continent from the Weddell Sea to McMurdo Sound by way of the South Pole, arrived at Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, on June 1. In January 1915, before his ship, the Endurance, could reach Antarctica, it was frozen in the ice in the Weddell Sea. In February, with the Antarctic winter approaching, Shackleton ordered his crew to convert Endurance to a winter station and wait for spring. When spring came, however, the movement of the ice began to crush the ship's hull, and on October 24 she had to be abandoned. Shackleton and his party camped on a large ice floe, hoping it would drift toward land. In April of this year the ice floe broke in two and Shackleton ordered his crew into lifeboats. Five days later they reached Elephant Island. He decided that his crew's only hope of rescue was to get back to South Georgia Island, 700 miles away across the Southern Ocean. He took the strongest of the lifeboats, named the James Caird after one of the expedition's sponsors, strengthened it further for the ocean voyage, and set sail with five of his crew. After fifteen days of remarkable seamanship and skillful navigation through frigid and stormy seas they reached the uninhabited southern coast of South Georgia Island. Rather than risk a further voyage around rocky shores and dangerous seas to the north side of the island, Shackleton decided to travel by land with two of his crew across the mountain ridges, glaciers and snow fields of the island's interior, a feat no one had previously attempted. Thirty-six hours later they reached the whaling station at Stromness, where they were greeted by the manager. Shackleton's first question was "Tell me, when was the war over?" The manager replied "The war is not over. Millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad."

After he reached the Falklands, Shackleton moved immediately to rescue the twenty-two men left behind on Elephant Island. He attempted to reach the island on a steamer placed at his disposal by the government of Uruguay, but was forced to turn back by extreme ice conditions. At month's end he is back in Port Stanley planning another rescue attempt, this time with an ice breaker. He is optimistic that the men on Elephant Island can survive on short rations, supplemented by the many penguins that inhabit the island.

Li Yuan-Hung

June 1916 – Selected Sources and Recommended Reading

Contemporary Periodicals:

Contemporary Periodicals:

American Review of Reviews, July and August 1916

New York

Times, June 1916

Books and Articles:

Caroline Alexander, The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition

A. Scott Berg, Wilson

Britain at War Magazine, The Third Year of the Great War: 1916

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis 1911-1918

John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography

John Milton Cooper, Jr., The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt

Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis 1911-1918

John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography

John Milton Cooper, Jr., The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt

Patrick Devlin, Too Proud to Fight: Woodrow Wilson's

Neutrality

John Dos Passos, Mr. Wilson's War

David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East, 1914-1922

Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life

Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History

Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History

Martin Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, Volume One: 1900-1933

Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill Volume III: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916

Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill Volume III: The Challenge of War, 1914-1916

Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, Decisions for War, 1914-1917

Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House

Paul Jankowski, Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War

Keith Jeffrey, 1916: A Global History

Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography

John Keegan, The First World War

David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society

Nicholas A. Lambert, Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War

John Keegan, The First World War

David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society

Nicholas A. Lambert, Planning Armageddon: British Economic Warfare and the First World War

Arthur S. Link, Wilson: Confusions and Crises, 1915-1916

Arthur S. Link, Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era,

1910-1917

G.J. Meyer, A World Undone: The Story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918

Merlo J. Pusey, Charles Evans Hughes

Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict

J. Lee Thompson, Never Call Retreat: Theodore Roosevelt and the Great War

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History

The West Point Atlas of War: World War I